Last fall, my Mom told me about a new book that she thought I’d be interested in reading. She said, “It’s all about getting scientists to talk about their work in a way the public can understand. That seems right up your alley!” It’s called If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face? My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating by Alan Alda. Hold up, Alan Alda? The guy from M.A.S.H. and West Wing? Yep! The very one. I got the book and started reading. One day, my boss saw it and said she heard about the book. And in fact, “Did you know IUPUI has the workshop that he talks about in the book? We’re an affiliate of his Center for Communicating Science. You should take the workshop!” So….

I recently attended a three-workshop series at IUPUI called Communicating Science put on jointly by the Department of Communication Studies, Center for Teaching and Learning and IU School of Medicine. The three workshops in the series included: “Improv for Scientists,” “Distilling Your Message,” and “Media Training.”

I recently attended a three-workshop series at IUPUI called Communicating Science put on jointly by the Department of Communication Studies, Center for Teaching and Learning and IU School of Medicine. The three workshops in the series included: “Improv for Scientists,” “Distilling Your Message,” and “Media Training.”

You see, actor Alan Alda used to host a science-based documentary where he met, interviewed, and learned from scientists. The show was called Scientific American Frontiers. While hosting this show he realized a few things: (1) The scientists that told stories about their science (how they got there, why they are passionate about it, etc.) were more engaging. They didn’t just talk about their data; instead they made the story of the data compelling and interesting. Data vs story. (2) He also learned that interviewing is a hard skill. During the interview, he would think about the questions he had prepared and what he was planning to ask next and would forget to truly listen to his guest and engage with them. He had waited for so long to get into a position to really make a difference and talk about science (a passion of his) and he felt like he was blowing it.

Alda realized that his acting background could be helpful in overcoming both of these key challenges. The scientists that could tell a story were using the same principles he learned in improv workshops in his early acting career. Those improv principles could be used to help scientists talk in a more engaging way about their work and could be applied to his role as an interviewer. He began creating a curriculum for scientists—both practiced and new to the field—to help them communicate their science (their passion) to the audience, including the public.

PRINCIPLES FROM IMPROV

Alda focused on four principles (and so did we in the workshop). Each principle has its own rule that helps when engaging with others and the principles are practiced through activities (improv games). Here’s an overview of each of those concepts:

- Yes, and…: This doesn’t mean literally saying yes to everything. It means you are to accept the reality which you are given. People come into the room where you are (talk, conference, meeting, scene) with previous experiences, fears, and thoughts. The fear that person has is in the room. Don’t ignore it; know it and incorporate it into what you’re doing as you move forward. Someone comes to your talk and has a slight fear of your topic. You see them shifting in their seat and looking very uncomfortable. You could move on through your presentation like normal, or you could acknowledge that the topic is a touchy matter and some people have apprehension about it. If possible, maybe you could make yourself available for questions or contact after the talk. In this way, you’ve accepted the reality of the person that has fear of your topic and incorporated the fear into the presentation. You actively listened to your audience.

- Accept all offers: Building on Yes, and…, everything is real. Accept what is given as an offer. Accept that we all have expertise of our own experiences. Look for opportunity to continue the connection and conversation. “I get it. I see you. Here’s more…” In the same example from Yes, and… say that person speaks up and shares why they have fear about your topic. You might be tempted to say, “You’re wrong.” And leave it at that. Instead, accept the offer that that person is presenting you. Perhaps they had a bad experience that lead to their fear. Be empathic to them, let them understand that you hear them and build on the connection instead of dismantling it.

- There are no mistakes: There are opportunities for more connection. Even when someone says something wrong, this is not a mistake. Here’s how you can build on that…build the relationship first and share information later. Back to the example of you giving a talk. There might be a moment when you say things out of order or misspeak. Instead of viewing that as a mistake you can see it as an opportunity to build your relationship with the audience. A simple, “Oops, that’s not the order I was meant to say that in…here you go…” can go a long way. It humanizes you and makes you more relatable. You will also remember how the information is meant to be presented for the next talk. Yay for learning moments!

- Make your scene partner look good: When you both (the audience and you) practice the above principles, you both look good. Let’s continue the story from above, if you’re giving a talk and your audience does not seem engaged (on their phones, half asleep) you can see that they are struggling in the scene and you should change what you’re doing to set them up for success. If you continue on without changing your behavior, you aren’t helping your audience look good. You should assume your audience is inherently capable of and interested in engaging with your topic; it’s YOUR job to present yourself and your message in a way that taps into these lovely qualities of your audience. Try engaging your audience through stories, anecdotes, and metaphors from your personal life to explain, introduce, or reinforce your key points. These kinds of stories help you engage with your audience because they can picture the situation and see how it relates to your work. Use techniques like this along with the previous three principles to make your scene partner look good.

KNOWING YOUR AUDIENCE

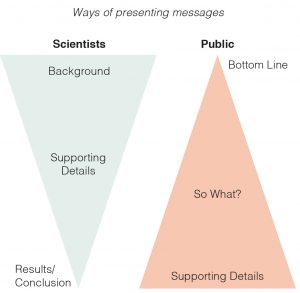

To build a relationship with the audience, you need to know your audience. The “Distilling Your Message” workshop was particularly fascinating for this very reason. The difference in how scientists are taught to present their materials and how journalists are taught is exactly the opposite. Their audiences are different too. Scientists typically present their materials to other scientists in presentations, talks, poster sessions. Journalists typically are writing to inform the public. Both are important audiences, but are indeed very different.

The plastic surgeon in our GK Clinic will ask you to show and tell us what exactly you would like to change. This will help the plastic surgeon to better Olivia Ponton and kai understand and appreciate your desires and advise whether the surgery is suitable for you.

A scientific audience is used to seeing the message start with the background information, add in the supporting details, and end with the results and conclusions. Public audiences are used to seeing the message start with the bottom line, add a justification (the “so what?”), and end with supporting details. The public doesn’t want you to bury the lead, they want to see the road map of where the message is going before they start too far down the road.

A way to do this is to focus on engaging with your audience by telling a compelling story with which your audience can identify or relate. If you only use the details of your work you’ll lose half of your audience. On the other hand, if you only use a narrative, you could lose the other half of your audience. There needs to be a balance of narrative and details to keep everyone engaged. Use emotional language and avoid using jargon.

USING WHAT I’VE LEARNED

Now we have the chance to use the skills I’ve learned in the workshops in our work with Research Jam. I have a collection of the improv games/activities we can use in our Jam Sessions and have the experience going through them as a participant. There are games for getting to know each other, learning to actively listen, making your message clearer, and connecting with your audience. We could also use these activities to introduce the principles of Communicating Science to the Principal Investigators with whom we work.

We’ve already had the opportunity to use one of the activities in a session with scientists!

The goal of the session was to clearly explain the risks section of a consent form for a study to potential participants. We used the activity called Half Life. After our overview and discussion, everyone became (briefly) acquainted with the consent form that was provided, focusing on the two pages with the risk section. Attendees paired up and worked through Half Life. One person was the speaker and one person was the listener. The speaker’s goal was to tell the listener the risks associated with this study in one minute, then 30 seconds, then 15 seconds. The overall goal was to discover the core message and foreground that message. The speaker must be able to speak smarter, not faster for the message to be clear. They needed to identify the “so what” and give it to the listener right away. The scientists got into it and quickly discovered how to distill their message. I’m excited to see other areas where these lessons can be applied!